Bladder cancer affects almost 3,000 Australians each year and causes thousands of deaths. Yet it often has a lower profile compared to other types of cancer such as breast, lung and prostate.

The rate at which Australians are diagnosed with bladder cancer has decreased over time, which means the death rate has fallen too, although at a slower rate. This has led to an increase in the so called mortality-to-incidence ratio, a key statistic that measures the proportion of people with a cancer who die from it.

For bladder cancer this went up from 0.3 (about 30%) in the 1980s to 0.4 (40%) in 2010 (compared to 0.2 for breast and colon cancer and 0.8 for lung cancer). While the relative survival (survival compared to a healthy individual of similar age) for most other cancers has improved in Australia, for bladder cancer this has decreased over time.

Who gets bladder cancer?

Australia’s anti-smoking measures and effective quitting campaigns have led to a progressive reduction in smoking rates over the last 25 years. This is undoubtedly one key reason behind the observed decline in bladder cancer diagnoses over time. Environmental risk factors are thought to be more important than genetic or inherited susceptibility when it comes to bladder cancer. The most significant known risk factor is cigarette smoking.

Bladder cancer risk also increases with exposure to chemicals such as dyes and solvents used in industries like hairdressing, printing and textiles. Appropriate workplace safety measures are crucial to minimising exposure, but the increased risk of occupational bladder cancer remains an ongoing problem.

Certain medications, such as the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide, and pelvic radiation therapy have also been linked to bladder cancer. Patients who have had such treatment need to be specifically checked for the main symptoms and signs of bladder cancer, such as blood in urine.

Men develop bladder cancer about three times as often as women. In part, this may have to do with the fact that men are exposed more to the risk factors. Conversely, women have a relatively poorer survival from bladder cancer compared to men. The reasons for this are unclear, but may partly relate to difficulties in diagnosis.

Read more – Interactive body map: what really gives you cancer?

How is bladder cancer diagnosed?

At present, unlike other cancers such as breast cancer that can be picked up on mammograms, bladder cancer can’t be diagnosed at the stage where there are no symptoms. The usual symptoms that lead to the diagnosis of bladder cancer are blood in the urine (haematuria) or irritation during urination, such as frequency and burning.

But symptoms are quite common and, in most instances, caused by relatively benign problems such as infections, urinary stones or enlargement of the prostate. So, the key to bladder cancer diagnosis is for suspicious symptoms to be quickly and appropriately assessed by a doctor.

Haematuria, in particular, always needs to be considered a serious symptom and investigated further. Up to 20% of patients with blood in the urine will turn out to have bladder cancer. Even if the bleeding occurs transiently, this could still be the first symptom that leads to the earliest possible diagnosis of bladder cancer. It shouldn’t be ignored, since delayed diagnosis of bladder cancer is known to worsen treatment outcomes.

Unfortunately, delays in investigation of blood in urine are well known to occur and particular subgroups such as women and smokers tend to experience the greatest delays.

Recent studies from Victoria and West Australia have shown how some Australian patients have significant and concerning delays in investigation of urinary bleeding. Multiple factors contribute to such delays, including public perception and anxiety, lack of referral from general practitioners and administrative and resourcing limitations at hospitals.

Patients reporting blood in their urine should be referred for scans such as an ultrasound or computerised tomography (CT) to assess the kidneys. They should also have their bladder examined internally (cystoscopy) using a fibre-optic instrument known as a cytoscope. Cystoscopy, a procedure usually performed by urologists (medical specialists of urinary tract surgery), remains the gold standard for diagnosing bladder cancer.

Although diagnostic scans can help detect some bladder cancers, they have significant limitations in detecting certain types of tumours.

What happens if cancer is detected?

If a bladder cancer is noted on cystoscopy, it is removed and/or destroyed using instruments that can be passed into the bladder alongside the cystoscope. These procedures can be carried out at the same setting or subsequently, depending on available instruments and anaesthesia.

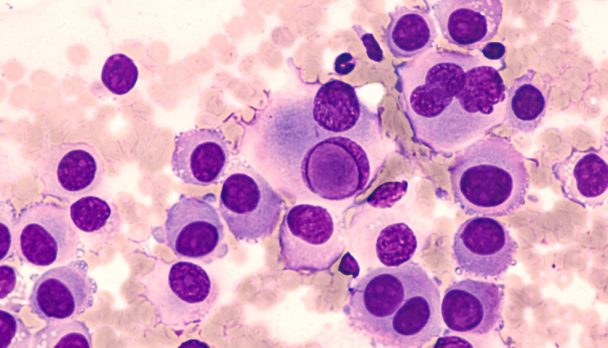

The cancerous tissue removed is examined by a pathologist to confirm the diagnosis. This also provides additional information such as the stage of the cancer (how deep it has spread) and grade (based on appearance of the cancer cells), which help determine further management.

Are there any new developments?

Given that cystoscopy is an invasive procedure, there has been considerable effort to develop a non-invasive test, usually focusing on markers in the urine that can indicate the presence of cancer. To date, none of these have been reliable enough to obviate the need for cystoscopy.

Read more: Can we use a simple blood test to detect cancer?

Additionally, to enhance the ability to detect small bladder cancers, cystoscopy using blue light of a certain wavelength (360-450nm) can be combined with the administration of a fluorescent marker (hexaminolevulinate) which highlights the cancerous tissue. While this approach does lead to the detection of more cancers, the resulting clinical benefit remains uncertain.

At present, immediate and appropriate investigation of suspicious symptoms, especially haematuria, using a combination of radiological scans and cystoscopy, remains the best means to diagnose bladder cancer in an accurate and timely manner.

Shomik Sengupta, Professor of Surgery, Eastern Health Clinical School, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

At present, immediate and appropriate investigation of suspicious symptoms, especially haematuria, using a combination of radiological scans and cystoscopy, remains the best means to diagnose bladder cancer in an accurate and timely manner.

Shomik Sengupta, Professor of Surgery, Eastern Health Clinical School, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Expert/s: Shomik Sengupta