Articles / Bulk-billing incentives: it’s a trap

writer

General Practitioner, Belgravia Medical Centre, Perth

Various medical groups have welcomed the federal budget for 2023-24 and lauded the government for its long overdue investment in primary care. However, behind the headline numbers is a policy change that further erodes one of the key principles of Medicare – its universality.

The most significant change announced in the May budget was the increase of the bulk-billing incentive for persons with healthcare/concession cards, pensioners and children. GPs have long argued that the Medicare rebate is insufficient to cover their costs of service, and over the years have increasingly subsidised the cost to patients.

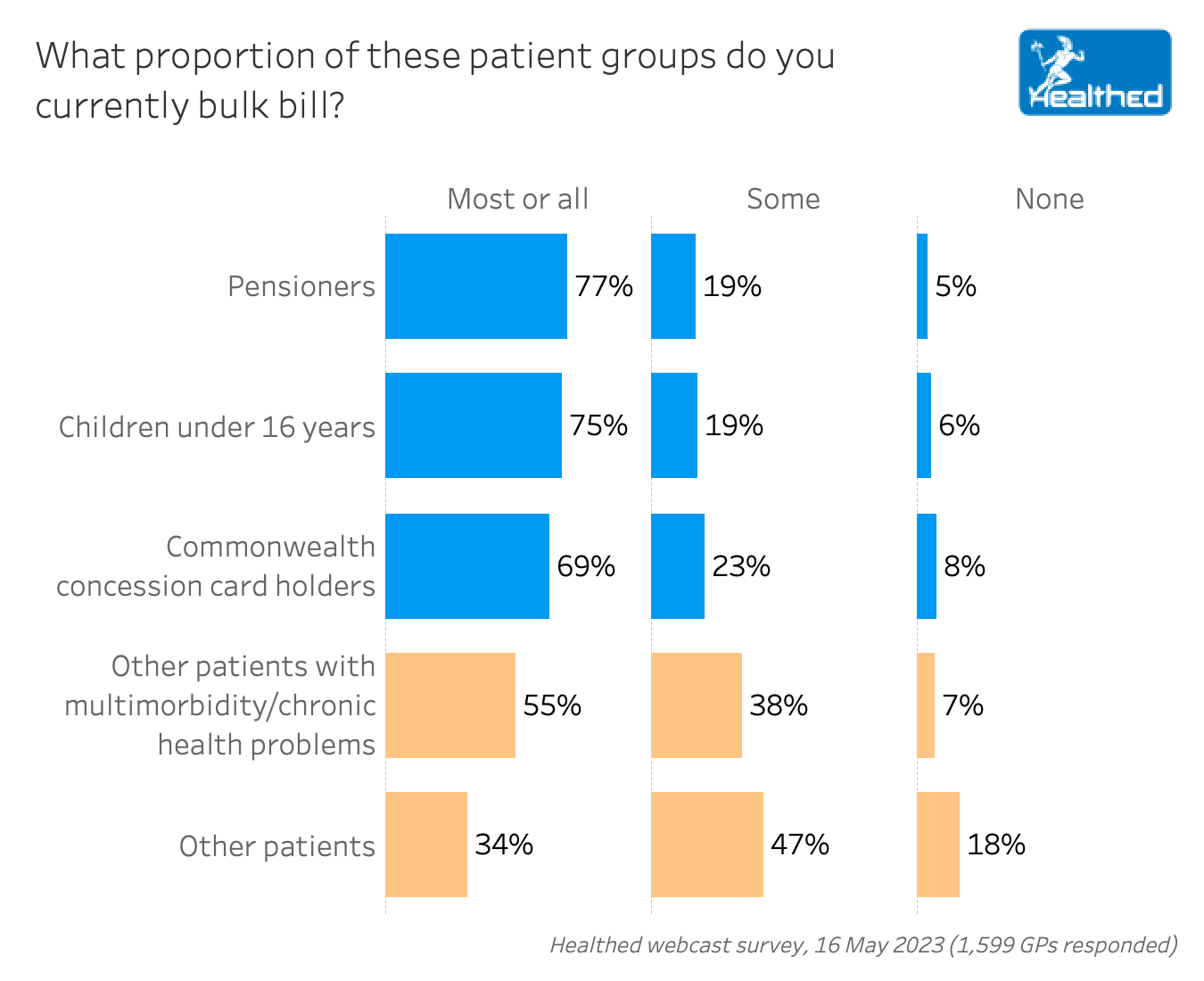

Consequently, many GPs have abandoned universal bulk-billing and moved to a mixed billing model. Bulk-billing rates are plummeting, according the 2022 RACGP Health of the Nations Report and Healthed survey data which has tracked the trend since 2021.

“The bulk billing incentive is clever politics but poor policy. If it’s successful, the government can take credit, and if it fails, GPs can be blamed….It shifts the blame rather than improving access to health care.”

To its credit, the government has acknowledged this deficit, but its response suggests it is intent on selectively targeting particularly vulnerable groups in the population, rather than upholding the original vision of universal access to healthcare.

A Healthed survey when the policy was announced found that the vast majority of GPs are already bulk-billing the groups targeted for the incentive, calling into question how much scope there is for improvement. About three quarters of more than 1200 surveyed GPs said they currently bulk-bill most or all children under 16 and pensioners.

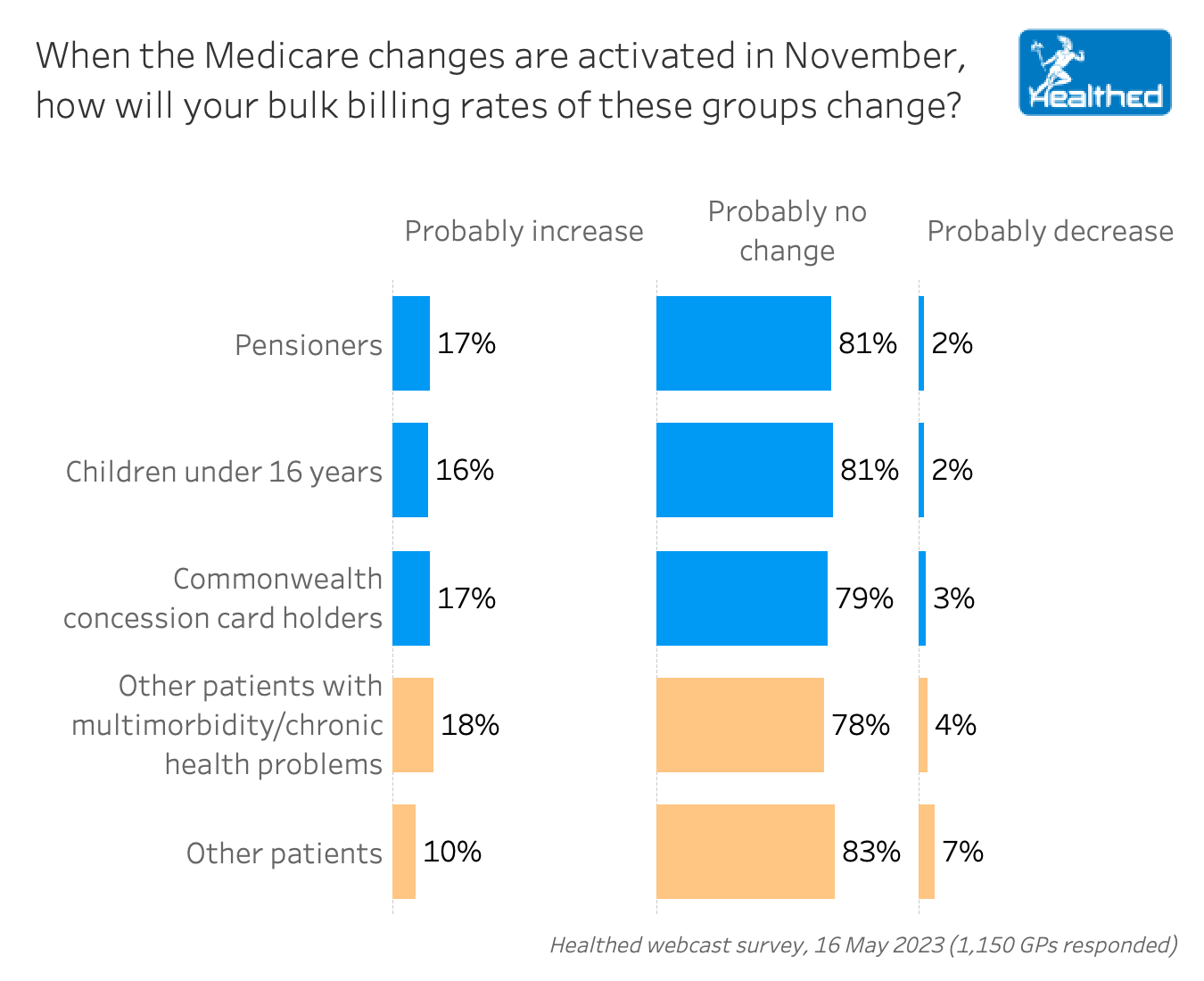

In effect, the selective targeting of the incentives will contribute to an increasingly two-tiered system. It produces a ‘thin’ universality. Why? Universal access to care via bulk billing will only improve if GPs consider the incentive payments sufficient to meet the cost of providing the services to patients.

But look at the quantum of money that the government is giving urban GPs; it is roughly a $20 increase on the current rate. Yet the average out-of-pocket cost for a standard level B consultation in 2022 was $40.70. Hence a shortfall of $21 remains— which the government hopes GPs will absorb by accepting the incentive.

The increase is not to the rebate, so it does not go to patients. Therefore, if a GP chooses not to bulk bill, the $20 payment of the incentive is effectively ‘lost’ to the patient. They either pay $41 out of pocket or nothing (if bulk billed). The in-between option of $21 is surrendered with this policy. This forces GPs to decide who can access services without an out-of-pocket expense.

The politics of this is insidious: government policy is creating a two-tiered system, but the onus falls on GPs to effectively implement this thin universalism. Some will absorb the cost while others will leave the system altogether. It might be good politics, but it is bad policy that undermines the universality of the Medicare system.

Which statement best sums up your views of the Medicare changes?

“These measures are a trap—clever politics so that the government can take credit for improvements, but blame GPs if bulk-billing rates don’t improve.”

-14% of surveyed GPs.“These measures are superficial or cosmetic changes that are unlikely to shift the downward trajectory of bulk billing.”

-18% of surveyed GPs.“These measures are a step in the right direction, but much more is needed.”

-52% of surveyed GPs.“These measures are a positive change that signals a sincere commitment to fix the system and return to the original vision of Medicare.”

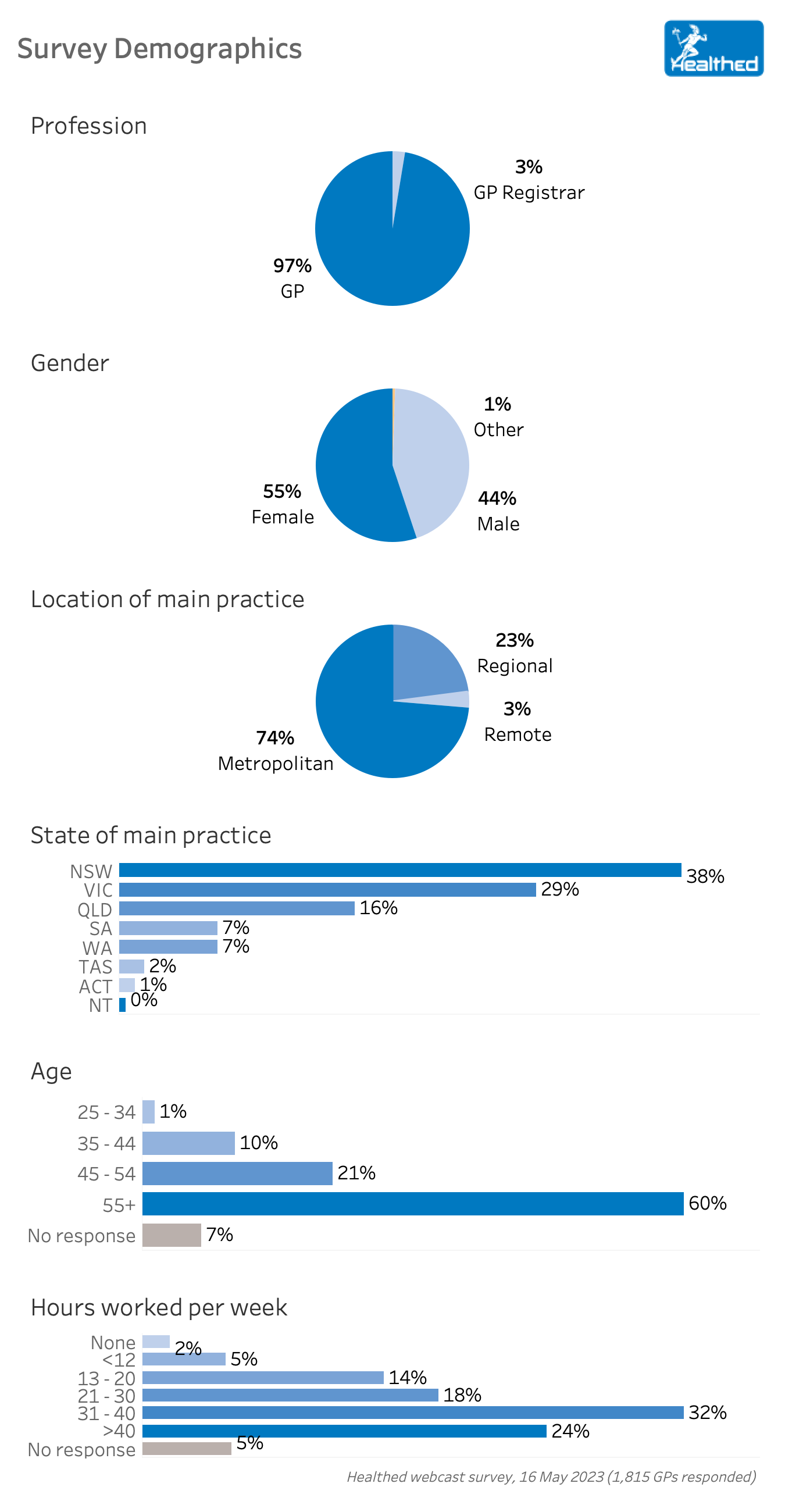

-10% of surveyed GPs.Source: 16 May 2023 Healthed survey of 1224 GPs across Australia

This policy will further undermine the doctor patient relationship that is at the heart of primary care and hasten the corporatisation of general practice where these decisions will be made in a boardroom rather than at the point of care.

The other problem is that the payments don’t address the issue of quality. The perennial criticism of fee for service is that it rewards high turnover medicine at the expense of quality. The payment encourages and supports shorter consults as the cost of 6-minute consultation is exactly the same as 20 minutes. Inevitably, there will be some practices that will embrace this change because it will increase their remuneration.

The government no doubt hopes that market forces will then force other GPs to follow suit, but unfortunately, the net result could be that GPs who provide longer consultations will lose out and quality of care will be eroded.

If the aim is to increase bulk billing, the policy is a risky proposition for the government. It relies on variables and assumptions it cannot control.

The government has grappled with these issues in the past. The key difference this time is that many GPs have already changed their billing policies out of financial necessity, and the workforce shortages and heightened demand negate the effect of competition. It is sobering to note that almost 20 years ago in a more conducive climate for change, a similar initiative to reduce the out-of-pocket expenses largely failed.

In a nutshell, the bulk billing incentive is clever politics but poor policy. If it’s successful, the government can take credit and if it fails, GPs can be blamed, as already apparent in the public utterances of politicians. It shifts the blame rather than improving access to health care. It moves Australia closer to a tiered health system.

Survey conception and design – Dr Ramesh Manocha, Yasmin Clarke, Lynnette Hoffman

Survey analysis and visualisation – Yasmin Clarke

Writing and reporting – Clinical A/Prof Pradeep Jayasuriya

Editing – Lynnette Hoffman

MHT For Women With History or Risk of Cancer

Muscle Health in the Elderly

GLP-1s For OSA

Oral Corticosteroid Stewardship For Asthma – Why it is Important

writer

General Practitioner, Belgravia Medical Centre, Perth

Strongly agree

Somewhat agree

Neutral

Somewhat disagree

strongly disagree

Listen to expert interviews.

Click to open in a new tab

Browse the latest articles from Healthed.

Once you confirm you’ve read this article you can complete a Patient Case Review to earn 0.5 hours CPD in the Reviewing Performance (RP) category.

Select ‘Confirm & learn‘ when you have read this article in its entirety and you will be taken to begin your Patient Case Review.

Menopause and MHT

Multiple sclerosis vs antibody disease

Using SGLT2 to reduce cardiovascular death in T2D

Peripheral arterial disease