Articles / Assessing and managing heavy menstrual bleeding

writer

Obstetrician & Gynaecologist; Director, Women’s Health Road; Clinical Senior Lecturer, Macquarie University; VMO Macquarie University Hospital and Hornsby Ku-ring-gai Hospital

0 hours

These are activities that expand general practice knowledge, skills and attitudes, related to your scope of practice.

0.5 hours

These are activities that require reflection on feedback about your work.

0 hours

These are activities that use your work data to ensure quality results.

These are activities that expand general practice knowledge, skills and attitudes, related to your scope of practice.

These are activities that require reflection on feedback about your work.

These are activities that use your work data to ensure quality results.

Others don’t realise that effective treatments are available. The impact on women’s quality of life can be profound, but proper treatment usually results in remarkable improvements.

In practical terms, heavy menstrual bleeding is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss that interferes with a woman’s physical, social, emotional or material quality of life.

This could be a teenager taking time off school, curled up in bed, unable to attend sport. Or it could be a woman who cannot focus at work because her heavy periods have led to iron deficiency. Some women, like those who are vegetarian, might have lower iron reserves to begin with, and develop symptoms with what might be considered “normal” blood loss in others.

This definition is purposefully broad. It casts a wider net to capture the varied experiences of women whose lives are disrupted by their menstrual bleeding, regardless of the actual volume of blood lost.

At least one quarter of reproductive-age women report heavy menstrual cycles often or always. This is a massive number. Among adolescents and perimenopausal women, the prevalence is even higher—up to 33%. Some data suggests that when women are proactively asked, the rate might be as high as 50%.

Yet heavy menstrual bleeding is chronically under-recognised—by women themselves who stoically “get on with it,” by many clinicians who care for them, and by society, which often trivialises and stigmatises menstrual health.

Healthcare providers have a responsibility to change the perception that heavy bleeding is a normal part of being female.

Half of women with heavy menstrual bleeding experience associated pelvic pain. Some have underlying adenomyosis or endometriosis, but pain can occur without either of these conditions.

Women might also present with symptoms that reflect underlying pathologies such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, bleeding disorders, thyroid disease or other contributing conditions.

And of course, the consequences of heavy bleeding often include iron deficiency or anaemia, leading to fatigue and other systemic effects that further diminish quality of life.

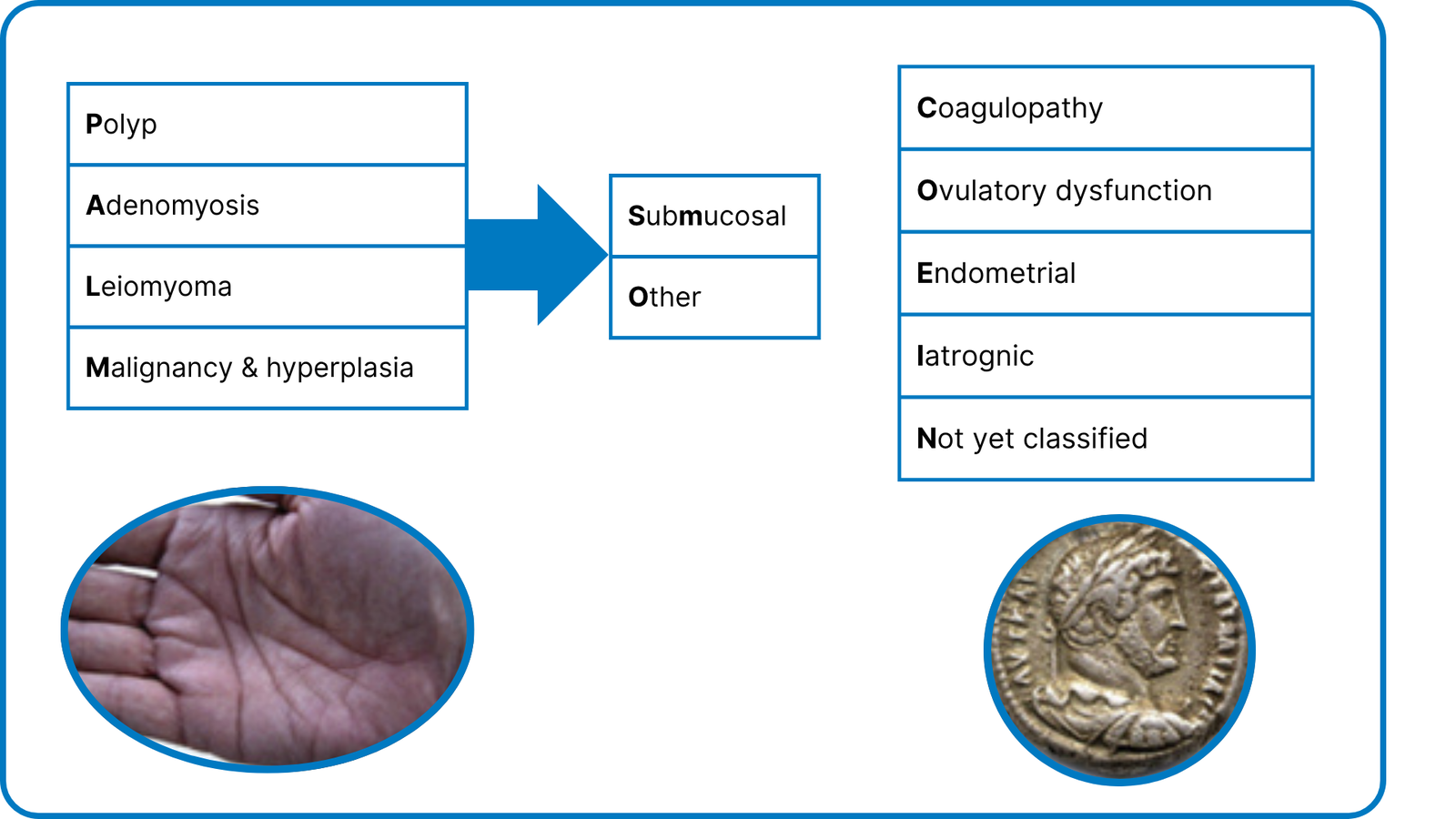

The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has developed a helpful classification system for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding, called PALM-COEIN.

The first acronym—PALM—refers to structural causes within the uterus:

The second acronym—COEIN—encompasses non-structural, often systemic causes:

Despite this comprehensive classification, it’s important to note there is no identifiable cause in roughly 50% of women with heavy menstrual bleeding, no matter how thoroughly it is investigated. This doesn’t mean their symptoms aren’t real or should not be treated—quite the contrary.

When a woman presents with symptoms suggesting heavy menstrual bleeding, it’s important to first acknowledge her symptoms. This is crucial because many women minimise their experience, saying things like “I just bleed for two days” or “it’s only the third day that’s bad”.

Assessment should include duration, regularity of cycles, and estimated volume of blood loss, categorising the flow as light, moderate, or heavy.

The following questions can help identify heavy menstrual bleeding:

After taking a comprehensive history, physical examination typically includes a speculum examination and bimanual examination (with permission and when appropriate). Modify this approach for women who aren’t sexually active or have other concerns.

There are three fundamental questions you’re trying to answer in the assessment:

The recently updated Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Clinical Care Standard emphasises that women should not leave their first consultation without a management plan.

A woman presenting with heavy menstrual bleeding should be offered medical management. Oral treatment should be offered at first presentation when clinically appropriate, including when a woman is undergoing further investigation or waiting for other treatment. This should include immediate options to relieve symptoms, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tranexamic acid, as well as hormonal options like an OCP or Mirena. Treatment should account for contraceptive needs if relevant and include a backup plan if the initial approach isn’t effective.

Hopefully, plan A will work wonderfully, but if not, be ready to move on. With over 19 options of care available—including medical, surgical and radiological treatments—it’s crucial to focus on improving quality of life, not the specific treatment method.

When you’re exploring HMB treatment options with women, consider:

NSAIDs: modest but helpful analgesia and flow control

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease prostaglandin production, reducing menstrual bleeding by about 30%—not the most effective option, but certainly helpful. Any bleeding reduction can make a difference when menstrual flow is heavy.

NSAIDs are multitaskers: they also help with dysmenorrhoea and have anti-inflammatory effects. Options include mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, and naproxen.

For best results, women should start NSAIDs the night before an expected period and continue taking them regularly through the first three or four days. However, NSAIDs should rarely be relied upon alone. Using them in combination with other treatments, such as tranexamic acid, may have a synergistic effect and yield better results.

Tranexamic acid: for heaviest flow days

Tranexamic acid is particularly effective for heavy menstrual bleeding. Remember “T is for tsunami”—it’s best used during the heaviest flow days. While it can be used for up to four days, most women find 48 hours of use sufficient.

Tranexamic acid reduces bleeding by 50-60%, making it an effective “low-hanging fruit” option for most patients. It’s a good first-line treatment while waiting for longer-term solutions like insertion of a levonorgestrel IUD.

Combined oral contraceptive pills: hormonal control

Lower dose COCPs may not adequately control heavy bleeding, so medium-dose COCPs (those containing 30mcg of ethinylestradiol, such as Levlen and Microgynon 30) are generally recommended for hormonal management.

Qlaira (oestradiol valerate/dienogest) is the only OCP with a specific indication for heavy menstrual bleeding, and has the highest evidence for blood loss reduction.

In some cases, especially when pain is an issue, continuous use is recommended, skipping the inactive pills. Off label-use of drospirenone-containing pills (such as Slinda) also achieves good results in some patients.

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS): the gold standard

The Cochrane database shows the levonorgestrel intrauterine device (Mirena, containing 52mg of levonorgestrel) is the most effective medical management for heavy menstrual bleeding. No other medical management option is as efficacious.

It typically takes up to three months from insertion to achieve real benefits, though many women report improvement even after their first cycle.

The main challenge is that the levonorgestrel IUD can disrupt women’s regular bleeding patterns. Some report spotting for two weeks or experiencing stop-start bleeding that can make it difficult to identify their actual period. Despite this, when blood loss is measured in research settings, it’s usually a fraction of the baseline volume.

Clinical data shows that by three months, blood loss can be reduced by about 86%, and HMB is typically reduced by more than 90% in most women by the six-month mark, and by up to 97% by 12 months—phenomenal results for women who may have been struggling for years.

It’s crucial that women are aware of this expected bleeding improvement with a Mirena so they can make informed treatment choices.

NICE guidelines recommend considering a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system as the first treatment for HMB in women who have:

Importantly, the Mirena is recommended for HMB management, not the Kyleena—which only contains 19.5 mg of levonorgestrel and is intended primarily for contraception.

Surgical options: when medical management isn’t enough

For women who don’t respond to medical management or who have specific structural uterine issues, several surgical options are available.

With so many treatment choices, it’s helpful to discuss the options, give women information to consider at home, and have them come back with any questions if they are undecided.

While generally considered a last resort, hysterectomy may be appropriate in women with significant structural abnormalities (like large fibroids causing pressure symptoms), or if there are concerns about cancer or pre-malignancy, such as atypical hyperplasia.

It may also be suitable when other HMB treatments have failed to control symptoms, or when a well-informed patient specifically requests this option.

The advantage is that hysterectomy provides a definitive tissue diagnosis and permanently resolves bleeding issues. However, lower-tier options should typically be tried first, especially given treatment advances over recent years.

The updated Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Clinical Care Standard no longer specifies waiting six months before referral. Instead, referral is recommended when:

Heavy menstrual bleeding affects women across all ethnic communities, but there are some variations worth noting. Fibroids, for example, are more common in women of African descent. In some cultural groups, the concept of shame or reluctance to seek timely care may be more prominent.

When encouraging women to seek care, we need to ensure culturally and linguistically diverse communities aren’t left behind and can access safe, supportive care.

Every year, charity Bleed Better hosts International Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Day on May 11 to raise awareness of this common and highly treatable issue.

Several excellent resources exist for both patients and healthcare providers:

RANZCOG offers a comprehensive heavy menstrual bleeding pamphlet

The Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Clinical Care Standard includes valuable consumer information

The “Bleed Better” campaign and International Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Day aim to raise awareness

RACGP also provides useful heavy menstrual bleeding resources

Based on this educational activity, complete these learning modules to gain additional CPD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder – Managing Challenging Behaviours

Paediatric Allergic Rhinitis & Immunotherapy

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency – The New Guidelines

Alcohol Addiction Assessment and Advice

writer

Obstetrician & Gynaecologist; Director, Women’s Health Road; Clinical Senior Lecturer, Macquarie University; VMO Macquarie University Hospital and Hornsby Ku-ring-gai Hospital

Increase

No change

Decrease

Listen to expert interviews.

Click to open in a new tab

Browse the latest articles from Healthed.

Once you confirm you’ve read this article you can complete a Patient Case Review to earn 0.5 hours CPD in the Reviewing Performance (RP) category.

Select ‘Confirm & learn‘ when you have read this article in its entirety and you will be taken to begin your Patient Case Review.